It is hard to believe that less than a year ago American Single Malt Whisky became an officially recognized and regulated category of spirit in its country of origin. What took so long?

January 19, 2025 was the effective first day for the new spirit type, and while single malts have been produced in the United States for almost four continuous decades now, federal recognition a standard of identity for the whisky type was a massive step. It was the culmination of years of hard work and advocacy by the American Single Malt Commission.

Thanks to their tireless efforts, American Single Malt is recognized as whisky that is produced from 100% malted barley, distilled in only a single distillery, matured in oak casks no larger than 700 liters, distilled to no higher than 80% abv, and bottled at a minimum of 40% abv. The whisky must also be mashed, distilled, and matured in the United States. Those basic standards define the category, leaving a lot of variables up to producers and bottlers.

The rules do diverge from single malt scotch in two important ways: there is no minimum age requirement and there is no restriction on still type for distillation. Single Malt Scotch must be matured for at least three years and distilled on a copper pot still (the use of patent or column stills means the product is a grain whisky, regardless of whether that grain happens to be barley.)

I would have preferred to see the American Single Malt rules mirror those of scotch a bit more; a minimum age feels appropriate, even if only one or two years. I understand that American regulations do not, in general, contain restrictions on age for general spirit categories, though special additional terms do convey a particular minimum maturation (“straight” whiskies required two years, and “bottled in bond” requiring four, among the other rules for their use). I also wish there was some ruling on the use of particular stills, not because I want to exclude small producers using multipurpose equipment, but because still type and shape have a significant influence on the spirit.

No doubt these were points where compromise was necessary and no single party was ever going to get everything they want– much less a random on the internet such as myself. The landscape of American Single Malt is very diverse and the American Single Malt Commission reflected that as it brought together many of the biggest names in the contemporary malt scene: Balcones, Copperworks, Westland, Westward, Virginia, etc. The list of member producers is a who’s who in the American Single Malt landscape and I am sorry to admit that I have never heard of, or tried whisky from, the vast majority of them.

Not yet anyway.

That is the real source of excitement for me when it comes to American Single Malt Whisky; there are so many producers out there, some of them dedicated to malt full-time, some part time, and others only occasionally or in an experimental capacity. Some of the operations are quite large and sophisticated, others are small and laborious. Some of the distilleries have backing and/or capital from giants in the spirits world, but most are independently run and operated.

There is so much to explore in the category and some of the distilleries have already charted new ground; combining techniques and flavor profiles from Scotland with local influences and ingredients: Clear Creek’s use of Oregon Oak, Copperworks’ use of heirloom barley varietals, or Santa Fe’s use of mesquite smoked barley, the list could go on!

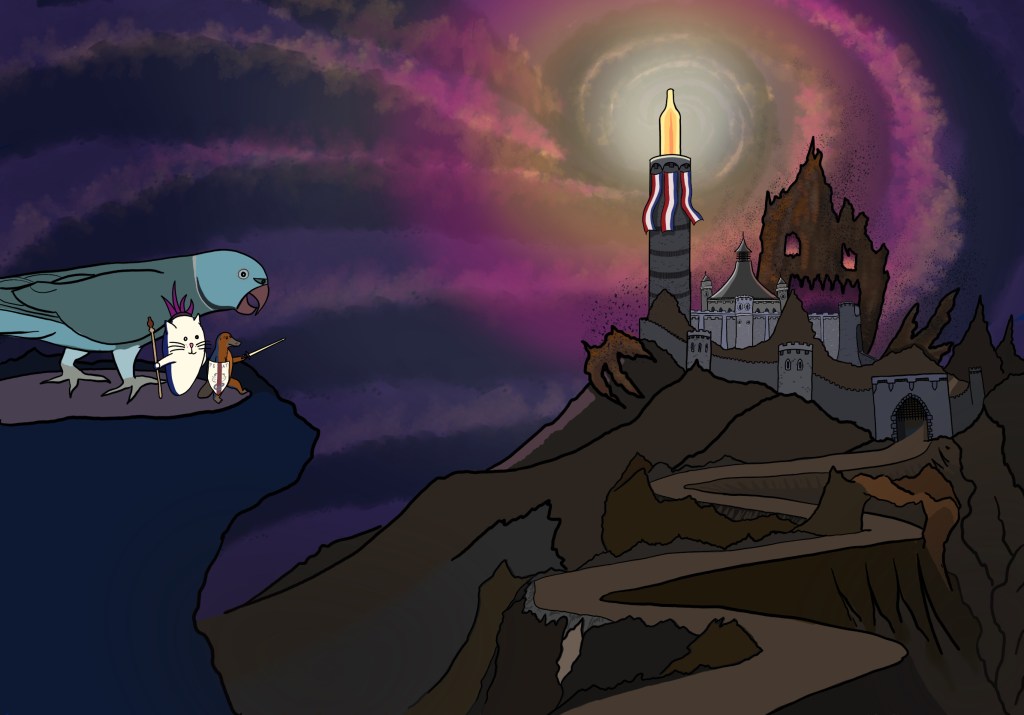

The art this week is inspired by one of the quibbles I have with many American Single Malt producers: an addiction to, or at least an over reliance on, new oak for flavor.

Yes, I quibbled on the category rules for American Single Malt a little bit, but I understand those. I am less forgiving of the wide spread use of new oak for maturation, especially initial maturation, and the attempt by many producers to recreate very bourbon-like flavor profiles. I think this practice muddies the category and chips away at the distinctiveness of the whisky.

After all, if one wants a big, oaky whisky, why pay more for single malt instead of bourbon? Let’s be real, most American Single Malts are priced higher than similar bourbon and have higher costs associated with production. If consumers are to be brought into the category, they need to think of it as something distinct and unique, with flavors and experiences they cannot get cheaper elsewhere.

So the artwork is a giant oak monster (with apologies to the Ents) which is attacking the palace of American Single Malts. It reflects my fear that the category may be unable to fully differentiate itself from bourbon and, as economic headwinds pick up, ultimately pay the price. Pessimism aside, there are producers using refill casks and types other than new oak, and those have largely been some of my favorites. I just hope we continue to see more innovation and experimentation on that front.

Artwork this week is my own: here we have the Turnip, Platypus, and giant Indian Ringneck facing the prospect of a great oak monster attacking American Single Malt. It is the first appearance of our pet bird, Hammy. I was originally going to use a more pastel color palette again, but ended up channeling something more like Dungeons and Dragons.

Leave a comment